Recently, we developed a model for gesture recognition using landmark positions determined by MediaPipe. The goal was to create an application that could be used as a virtual whiteboard, on which one could write or erase depending on the gesture and hand position.

After training a gesture recognition model, we realized that it was possible to improve prediction results without changing the model.

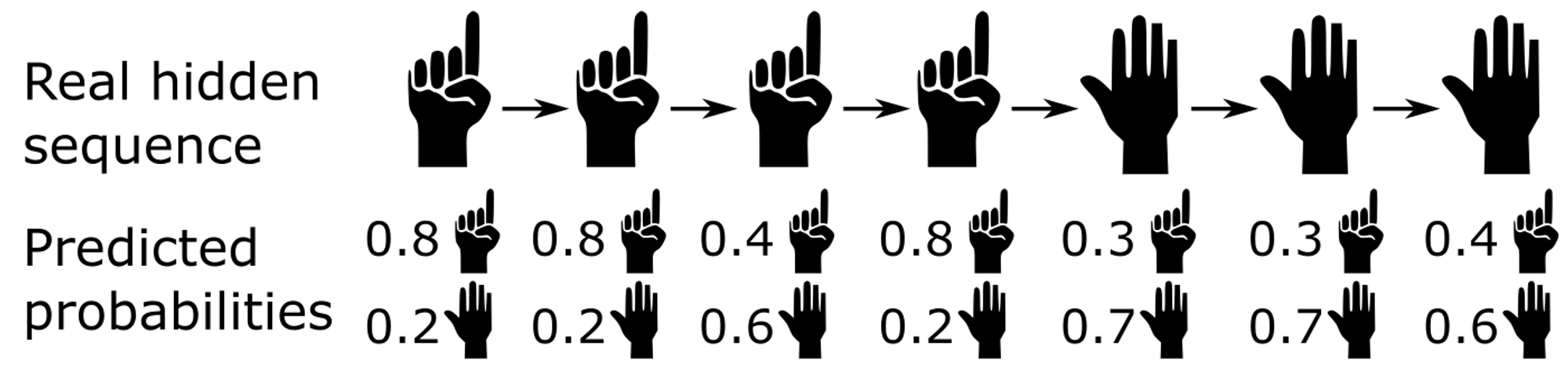

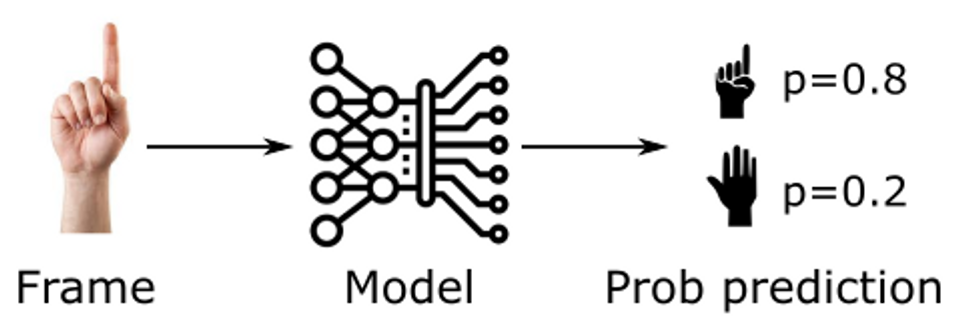

Consider the following example, in which a hand moves from making the gesture for the number one (“one”) to another gesture (“other”). At each frame, the model predicts the probability that the hand is executing the “one” or “other” gesture:

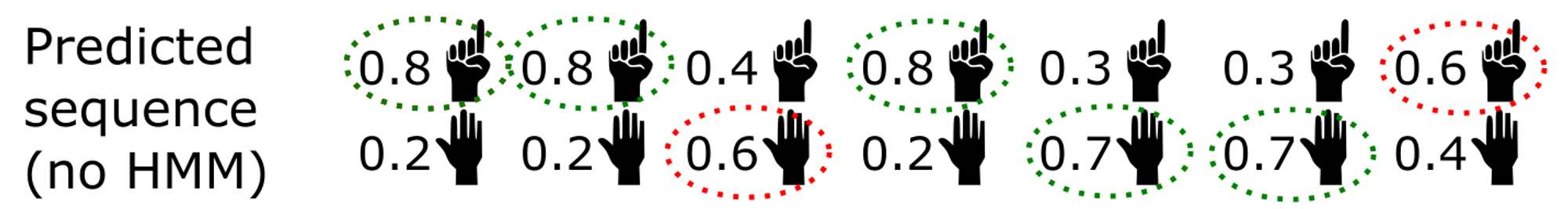

If we simply choose the highest probability at each frame, we would get the following predictions (with errors in red):

It can be seen that the error in the third prediction could easily be avoided. In fact, in steps 1, 2, and 4, the “one” gesture is predicted with a fairly high probability. On the other hand, the prediction in the third step provides “other” with a fairly low probability (60%).

It can be seen that the error in the third prediction could easily be avoided. In fact, in steps 1, 2, and 4, the “one” gesture is predicted with a fairly high probability. On the other hand, the prediction in the third step provides “other” with a fairly low probability (60%).

In general, it is unlikely that the hand will change gestures between two consecutive frames, and it is therefore intuitive that the prediction in step 3 is actually a model error. The gesture has not actually changed.

These are intuitive considerations, but how can we formalize and implement them effectively (hopefully in the best possible way) in an algorithm?

If you have read the title of this post, you already know the answer: using a Hidden Markov Model.

Some resources on Bayes’ Theorem:

- In-depth explanation: https://bayesmanual.com/index.html

- 15-minute video (3B1B): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HZGCoVF3YvM

- Other resources: https://letmegooglethat.com/?q=bayes+theorem

Gestures seen as Hidden Markov Model

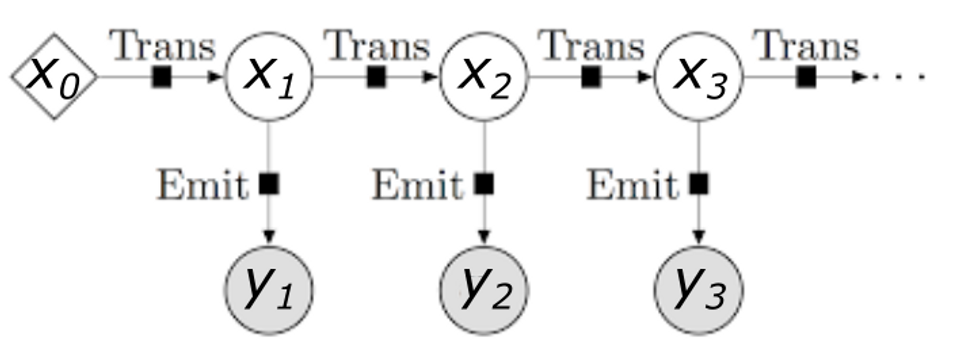

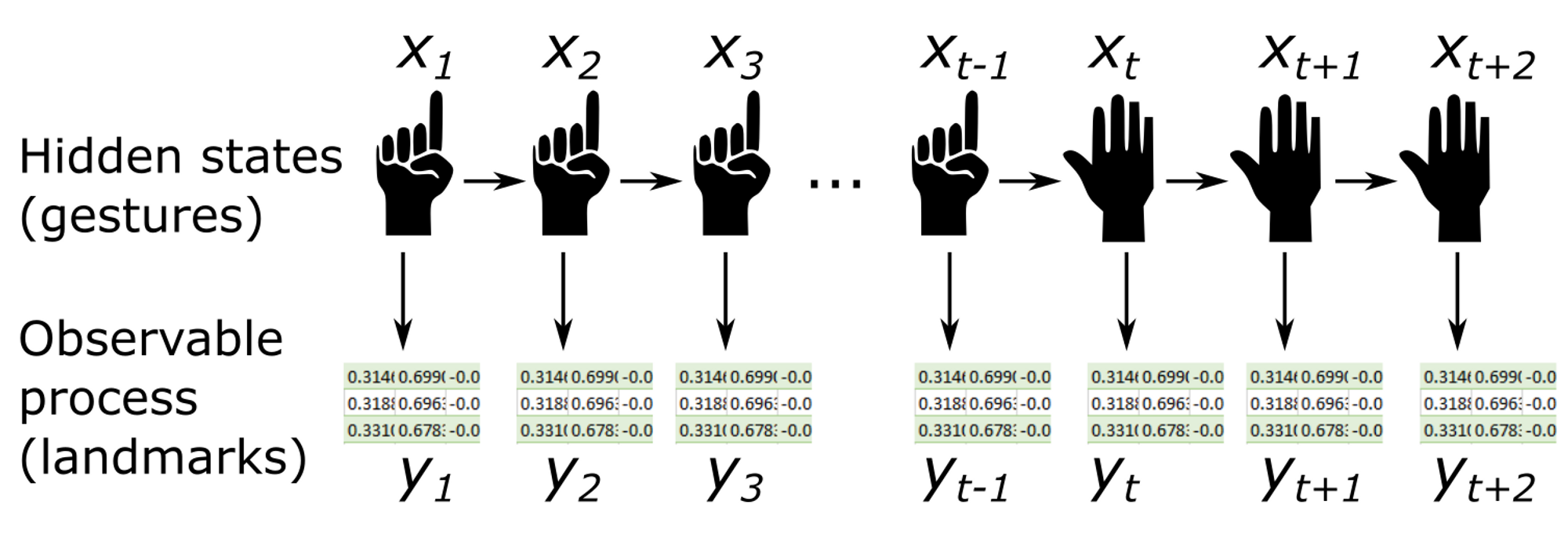

A hidden Markov model (HMM) is a statistical Markov model in which the system being modeled is assumed to be a Markov process $X$ — with unobservable (“hidden”) states where:

- The Markov process is assumed to have a finite number of states;

- The states evolve according to a Markov chain (the probability of being in a certain state is determined by the previous state);

- Each state generates an event with a certain probability distribution that depends only on the state;

- The event is observable, but the state is not.

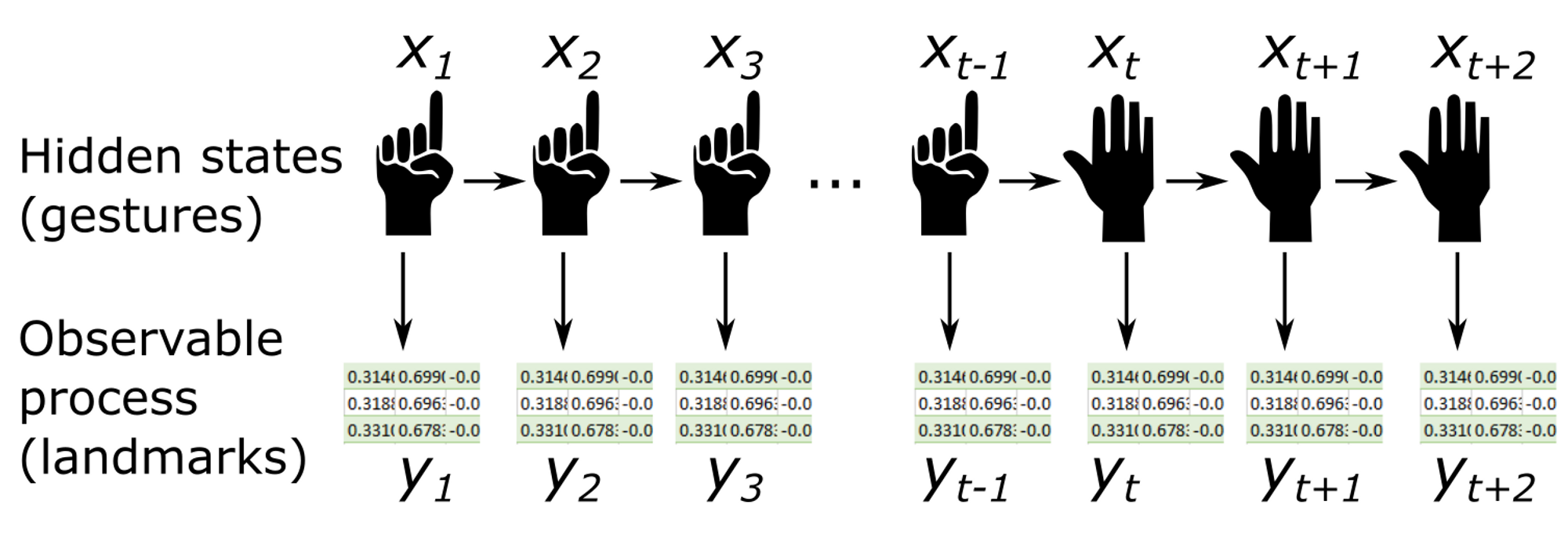

In our case, the hidden states $x_t$ are the different gestures. For simplicity, we consider only two gestures: “One” (raised middle finger and clenched fist) and “Other” (any gesture that is not “One”). In our example, we could use the “One” gesture to write, using the tip of our index finger as if it were a virtual pencil, and any other gesture would interrupt the writing on the board.

The states will transition at each frame in a given sequence, for example:

One → One → … → One → Other → … → Other → One → One → …

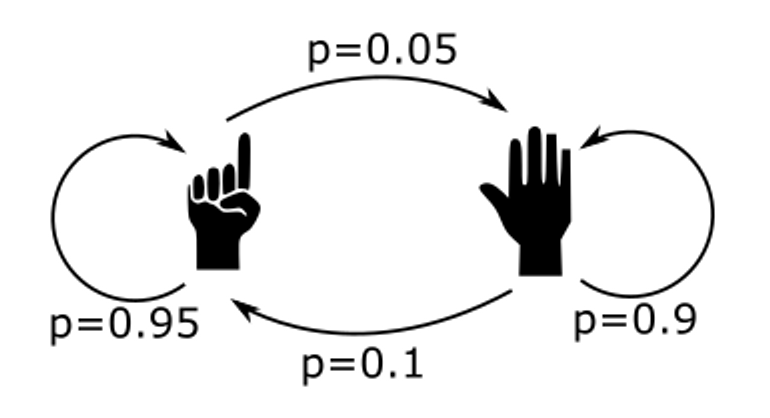

Suppose we know the probabilities according to which the state changes occur. Let’s forget about how to do it: we can imagine doing it using statistics on a dataset, or choosing the probabilities ourselves manually until the result satisfies us.

For example:

The transition matrix will be:

\[A=\left(\begin{array}{cc} 0.95 & 0.05\\ 0.1 & 0.9 \end{array}\right)\]where \(A= \left(a_{ij}\right)\) and \(a_{ij}\) the probability to change from a state \(i\) to a state \(j\).

One could argue that the gestures are not hidden at all, given that the hand is clearly visible in front of your eyes. However, from the application’s point of view, it is far from obvious, as it cannot actually know with certainty which gesture is being executed by the hand.

All it observes are the landmark positions obtained from running MediaPipe on the frame. These positions represent the observables $y_t$, which depend, with a certain probability distribution, on the states (i.e., the gestures) $x_t$.

Despite it may seem that all the ingredients are ready on the table (hidden states, transition matrix, and observables), if we want to exploit the information given by the observables, we need to know which probability links them to the hidden states. We need to know $P(y_t\mid x_t)$.

The answer comes from the last ingredient we have not yet added: the prediction model. As we said, we have trained a model that, for each frame, associates the probability that the gesture belongs to the “one” or “other” class (note that I am talking about probabilities, not logits. Probabilities are obtained through specific fitting or by normalizing the logits depending on the case, for example: https://datascience.stackexchange.com/a/31045).

The model’s result is the probability of having a certain gesture, based on the observed landmarks, i.e.,

\[P(x_t\mid y_t)\]This is precisely the opposite of what we need! How can we swap the two terms? By using Bayes’ theorem:

\[P(y_t\mid x_t)=\frac{P(x_t\mid y_t)}{P(x_t)}P(y_t)\]\(P(x_t\mid y_t)\) is easy; it’s the output of the model. \(P(y_t)\) is unknown and practically impossible to find. Fortunately, this is not a problem since we will find a way to simplify this term and remove it from our equations. Actually, what we really need is to be able to compare the probability of the observable for the different possible hidden states. The “a priori” probability of the observable $P(y_t)$ is always the same and will not, therefore, contribute to favoring one hypothesis over another. \(P(x_t)\) takes a little more reasoning to find. The basic principle of using HMM and, more generally, all Bayesian methods, is to replace the “a priori” of one’s model with more efficient “a priori.” In this case, the “a priori” we have chosen to use is the Markov chain and, more precisely, the transition matrix. In fact, what we want to do is make predictions that take these pieces of information into account. Therefore, the new “a priori” is the Markov chain, but what was the old one? What “a priori” about the state is used by the model if used without any filtering? If you think the answer is “none,” you are wrong: it is impossible not to have a “a priori.”

The answer is not so complex, beyond the features used by the model; there is another important piece of data used for predictions: the frequency of the state in the dataset. In fact, regardless of the observables, the model tends to predict states that are mostly present in the training dataset. This is the “a priori” used by the model, the information used to make the predictions. The value of $P(x_t)$ is the frequency of state $x_t$ in the training dataset.

In our case, we trained the model on four datasets of equal length, representing four different gestures (“one,” “closed hand,” “open hand,” “spiderman”). Therefore:

\(p(x_t=\mbox{"one"})=0.25\) and \(p(x_t=\mbox{"other"})=0.75\)

Now we are ready to implement our filter.

The Forward algorithm

For this part, I will mainly refer to the presentation made on Wikipedia ((https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forward_algorithm)), which I found clear and well-done.

If our basic model only calculates $p(x_t\mid y_t)$, what we want to do is include the information given by all the previous states, i.e., calculate

\[p(x_t\mid y_1,\dots,y_t)\]

Although the ultimate goal is to determine $p(x_{t}\mid y_{1},\dots,y_{t})$, we will use the algorithm to compute $\alpha_{t}(x_{t}):=p\left(x_{t},y_{1},\dots,y_{t}\right)/p\left(y_{t}\right)$, in order to simplify calculations in the induction process. To obtain the desired probability, we will apply:

\[\begin{align} p\left(x_{t}\mid y_{1},\dots,y_{t}\right) & = && \frac{p\left(x_{t},y_{1},\dots,y_{t}\right)}{p\left(y_{1},\dots,y_{t}\right)} \cdot 1\\ & = && \frac{p\left(x_{t},y_{1},\dots,y_{t}\right)}{\sum_{x_{t}}p\left(x_{t},y_{1},\dots,y_{t}\right)} \cdot \frac{p\left(y_{t}\right)}{p\left(y_{t}\right)}\\ & = && \frac{\alpha_{t}(x_{t})}{\alpha_{t}} \end{align}\]where $\alpha_{t}:=p\left(y_{1},\dots,y_{t}\right)/p\left(y_{t}\right)$.

In order to prove the recurrence, let:

\[\alpha_{t}(x_{t})=p\left(x_{t},y_{1},\dots,y_{t}\right)/p\left(y_{t}\right)=\sum_{x_{t-1}}p\left(x_{t},x_{t-1},y_{1},\dots,y_{t}\right)/p\left(y_{t}\right)\]Here we have used the fact that the various states $x_{t-1}$ (i.e., the possible gestures corresponding to frame $t-1$) are mutually exclusive, and at least one of them must occur.

The chain rule states:

\[p(A\cap B)=p(A\mid B)p(B)\]For three events $A$, $B$, $C$ we have:

\[\begin{aligned} p(A\cap B\cap C) & = && p(A\mid B\cap C)p(B\cap C)\\ & = && p(A\mid B\cap C)p(B\mid C)p(C) \end{aligned}\]Replacing in the above equation we get:

\[\alpha_{t}(x_{t})=\sum_{x_{t-1}}p\left(y_{t}\mid x_{t},x_{t-1},y_{1},\dots,y_{t-1}\right)p\left(x_{t}\mid x_{t-1},y_{1},\dots,y_{t-1}\right)p\left(x_{t-1},y_{1},\dots,y_{t-1}\right)/p\left(y_{t}\right)\]Let us consider the various terms of the product separately:

\(p\left(y_{t}\mid x_{t},x_{t-1},y_{1},\dots,y_{t-1}\right)\) is the probability of the observable \(y_{t}\) (landmark positions) given the hidden state \(x_{t}\) (gesture) and previous observables. However, the probability of \(y_{t}\) is actually completely determined by the hidden state, that is, the position of the landmarks depends solely on the gesture performed by the hand, and not on the positions in the previous frames. Therefore, \(p\left(y_{t}\mid x_{t},x_{t-1},y_{1},\dots,y_{t-1}\right)=p\left(y_{t}\mid x_{t}\right)\). As a result:

\[\begin{aligned} p\left(y_{t}\mid x_{t}\right) & = && \frac{p\left(x_{t}\mid y_{t}\right)p\left(y_{t}\right)}{p\left(x_{t}\right)}\\ & = && \frac{(\text{model output})p\left(y_{t}\right)}{\text{frequency of }x_{t} \text{ in the train}} \end{aligned}\]\(p\left(x_{t}\mid x_{t-1},y_{1},\dots,y_{t-1}\right)\) is the probability that the current state is $x_{t}$ knowing that the previous state is \(x_{t-1}\) and knowing the previous observables. Again, previous observables do not give us any additional information compared to \(x_{t-1}\). Therefore, \(p\left(x_{t}\mid x_{t-1},y_{1},\dots,y_{t-1}\right)=p\left(x_{t}\mid x_{t-1}\right)\) which is given by the corresponding term in the transition matrix.

$p\left(x_{t-1},y_{1},\dots,y_{t-1}\right)=\alpha_{t-1}\left(x_{t-1}\right)$, recalling the definitions, allows us to establish the inductive step in the recursion. Therefore, we get:

\[\require{cancel} \begin{aligned} \alpha_{t}(x_{t}) & = && \sum_{x_{t-1}}\frac{p\left(x_{t}\mid y_{t}\right)\cancel{p\left(y_{t}\right)}}{p\left(x_{t}\right)}p\left(x_{t}\mid x_{t-1}\right)\alpha_{t-1}\left(x_{t-1}\right)/\cancel{p\left(y_{t}\right)}\\ & = && \frac{p\left(x_{t}\mid y_{t}\right)}{p\left(x_{t}\right)}\sum_{x_{t-1}}p\left(x_{t}\mid x_{t-1}\right)\alpha_{t-1}\left(x_{t-1}\right) \end{aligned}\]Where \(p\left(x_{t}\mid y_{t}\right)\) is the model output, $p\left(x_{t}\right)$ is the frequency of state $x_{t}$ in the training dataset, $p\left(x_{t}\mid x_{t-1}\right)$ is the probability of transitioning from state $x_{t}$ to $x_{t-1}$, and $\alpha_{t-1}\left(x_{t-1}\right)$ is the output at the previous step of the algorithm.

The only missing piece is the induction base, namely the value of \(\alpha_{0}(x_{0})\). To establish it, we can exploit some property of the process, such as the probability with which the initial gestures occur. In our case, the process starts with the camera being turned on: since the “one” gesture corresponds to writing on the board, it is better to start with the “other” gesture to avoid unintended writing. Therefore, \(\alpha_{0}(x_{0}=\mbox{"one"})=0\) and \(\alpha_{0}(x_{0}=\mbox{"other"})=1\).

In any case, the impact of \(\alpha_{0}(x_{0})\) on the prediction process quickly dissipates after a few seconds and is therefore not a very important parameter, at least in our case.

Implementation

- You can find detail of the implementation in the Github repository *

Here a demo of the result:

It should be noted that filtering enables greater accuracy and stability in the results, even when the model makes mistakes in identifying certain frames as “Spiderman” or “closed hand

It should be noted that filtering enables greater accuracy and stability in the results, even when the model makes mistakes in identifying certain frames as “Spiderman” or “closed hand

Here the implementation of our class HMMFiltering:

class HMMFiltering():

def __init__(self, trans_mat, alfa_0, freqs, model):

"""

:param trans_mat: Transition matrix of the HMM

:param alfa_0: Initial values for alpha_t

:param freqs: Frequencies of the hidden states in model train dataset

"""

self.trans_mat = trans_mat

self.alfa_0 = alfa_0

self.freqs = freqs

self.alfa_t = self.alfa_0

def update_alfa(self, unfiltered_probs):

"""Calculate alpha_t+1 given the observation y_t"""

first_coeff = np.array(list(unfiltered_probs.values()) )/ self.freqs

second_coeff = 0

for i in range(len(self.alfa_t)):

second_coeff += self.trans_mat[i] * self.alfa_t[i]

self.alfa_t = first_coeff * second_coeff

# Normalize alfa_t to avoid numerical errors

self.alfa_t = self.alfa_t / sum(self.alfa_t)

def predict_proba(self, unfiltered_probs):

"""

Calculate the hidden state probability given the observation y_t.

Unfliltered_probs is a dictionary in the form {'name_gesture': prob, ...}

"""

classes = unfiltered_probs.keys()

self.update_alfa(unfiltered_probs)

return {gesture: prob for gesture, prob in zip(classes, self.alfa_t/sum(self.alfa_t))}

Virtual Whiteboard

Here an exemple of HMM filtering applied to our virtual whiteboard:

Plain model:

With HMM Filtering: